A tiny blonde with blue eyes and baggy blue slacks sits inside Painless Steel Tattoo and Body Piercing waiting to have her belly button pierced.

Amanda Mundt hopes to start stripping at the Fox Club in Missoula next month. A piercing will accentuate her look, she says.

Amanda Mundt hopes to start stripping at the Fox Club in Missoula next month. A piercing will accentuate her look, she says. Bouncing down Painless Steel’s black, red and white checkerboard floor, Mundt passes through a red door and says, “I can do this.”

Bouncing down Painless Steel’s black, red and white checkerboard floor, Mundt passes through a red door and says, “I can do this.” She pulls up her shirt exposing a flat, pale belly. One of the shop’s piercers, Anna Burns, charts the needle’s trajectory with a purple pen. A tattoo needle’s high-pitched whine from the next room accompanies Mundt’s deep breaths.

She pulls up her shirt exposing a flat, pale belly. One of the shop’s piercers, Anna Burns, charts the needle’s trajectory with a purple pen. A tattoo needle’s high-pitched whine from the next room accompanies Mundt’s deep breaths.Burns hovers above, wielding a thin silver needle between latex-covered fingers.

As the needle penetrates, Mundt’s breathing stops. She exhales deeply. The needle slides through the top of the navel’s upper lid and exits with a glint.

Burns plucks a pink barbell tipped with a cubic zirconium from a clear anti-bacterial solution and slides it through Mundt’s newly perforated navel.

The modern body-piercing trend in Missoula, if this Saturday afternoon is any indicator, is all about attitude.

“I want to piss off my mom,” said 20-year-old University of Montana student Julia Berkshire. She’s about to have the holes in her ears stretched to accommodate thicker jewelry. With gradual stretching, a pierced ear can become a nickel-sized window. “I’m sick of people thinking I’m just a girl. I’m tough.”

There are thousands of reasons to pierce the body, said James Weber, medical liaison for the Association of Professional Piercers.

“It’s sort of like asking someone why they wear the clothes they wear,” he said.

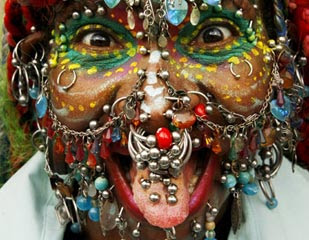

Body piercing is an ancient practice. Nose, tongue, ear and lip piercing all trace their roots back thousands of years through African, Aztec, Indian and Mayan civilizations. The Nez Perce, or “nose pierced,” were named so by the French because of the piercings worn by Indians. Warrior cultures over the years have embraced septum piercing, inserting thick pieces of bone, gold and jade into nose cartilage, which commanded a fierce presence on the battlefield.

For decades, piercings faded into the cultural background before resurfacing in the modern era.

Later, the American gay underground began toying with body jewelry. By the mid ‘80s, leather-clad street kids in European and American urban centers began sticking safety pins into sneering lips and furrowed brows. The accessory of rebellion was born.

The most common piercings, Burns said, are the nose and belly button, but she sees a lot of genitalia piercings too.

“I’ve done six or seven in the last week,” she said.

Once the mark of an outcast, Generation Y loves its metal.

“Now it’s weird if you don’t have it,” said Marin Addis, from behind the counter at Painless Steel.

It’s tough to gauge how many folks are pierced or who’s doing the piercing. Hairdressers, nail technicians and hipsters with needles, pierce for cash and for fun.

“That’s a big problem in the industry,” said Weber of the Association of Professional Piercers. “No one knows how many people are being pierced.”

In 2001, a Mayo Clinic poll conducted on New York college students reported that 51 percent had at least one body piercing. And a 2006 study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology found that 14 percent of people nationwide between the ages of 18-50 had a body piercing.

Even under the best conditions, medical complications arise, said dermatologist Amy Derick, who conducted the 2006 study. According to the poll, 24 percent of piercees had some sort of complication. Infection is not uncommon, and nearly a quarter of people with either a mouth or lip piercing reported breaking or chipping a tooth as a result.

Ashley Hutchinson quietly looks at the blue and pink nose rings in Painless Steel’s glass case.

“I’m such a wimp. I’m so scared,” she said. Her mother pierced her belly button, but it got infected, probably because of cheap jewelry, she said. Eventually the ring fell out. But with her brother’s encouragement and money (he’s paying for her new nose ring) she’s ready to try again.

“I’ve got all these horror stories in my head, like it will get infected and my nose will fall off,” Hutchinson said.

Piercing regulations vary from state to state. In Montana, no certification is required.

Painless Steel piercer Anna Burns has been at it for about six months and Paul Champion from Altered Skin Tattoo and Body Piercing for nearly 25 years. Both shops require blood-born pathogen and CPR training before a piercer goes to work.

While many of the folks at Painless Steel this Saturday afternoon are first-timers, it’s not unusual to see people with five, 10 or even 20 pieces of titanium imbedded in their skin. And as the trend spreads, it’s branching out.

“You’re just going to see more extremes,” Champion says.

If plain piercing isn’t enough, suspensions, or people hanging from their piercings, are becoming popular too. Folks are increasingly sticking finger-sized hooks into chest, leg and back piercings in order to hang from trees and poles.

Suspension in America today, like piercing, is largely a legacy of Native culture. The Sioux Indians used horn pegs and rawhide to suspend themselves during the annual Sun Dance Ritual.

Often, the ritual would take place over several days until hooks were ripped free. The pain and release cycle was thought to regenerate and bring practitioners closer to a higher power.

“The Sun Dance ritual is dedicated to God. In modern suspension, we do it for ourselves,” said Emryst Yetz from Rights of Passage, a multi-state organization dedicated to the practice.

Suspensions are largely about claiming one’s body and asserting individuality. But they are also, at times, as much about performance as transcendence.

Back at Painless Steel, Mundt leaps off of the piercer’s chair and dances in front of a wall-length mirror.

“I’m going to be a stripper,” she sings. “My grandfather would be turning over in his grave.”